Going out on a win

John Ashdown writes about his dad.

The Pinch gives writers a real opportunity to publish Blades content that wouldn’t appear anywhere else: that starts with paying them. Please consider signing up for a paid subscription so we can keep doing what we’re doing — huge thanks to all readers who do that already.

Words: John Ashdown

Saturday 19 March 2022, Barnsley (H)

It's quiet here. There’s no hustle or bustle, no whirring machines, no blipping heart-rate monitor – we're well beyond that. Dad lies in the bed looking thin and tired. Cancer – a rare, aggressive, bastard cancer – has brought us here, close to the end of the road. He can't eat, he can't take a sip of water without violently throwing it up. Conversation is whispered and short but he has still managed to charm the palliative care staff, testament to what I've also thought of as his Del Boy side, peaking through despite it all.

It's hard to know what to say. The day-to-day banalities seem more pointless than ever, mention of future plans comes with a giant unspoken asterisk. But right now, right at this moment, at a little after half four on a Saturday afternoon, it's easy to find the words. "Two-nil," I tell him, looking up from my phone. "Gibbs-White. But Sharp has gone off injured."

His smile at the goal turns into a wince. And I feel like an idiot. What am I doing, giving my dad injury news at a time like this? Come to think of it, what is he doing, caring about injury news at a time like this? But then it’s automatic, it’s just how we communicate, the way we always have. It’s why a few days later I find myself excitedly explaining to him, amid the kidney bowls and held-back tears, that United have signed Croatia international Filip Uremovic from Rubin Kazan to bolster their defensive options for the rest of the season.

Nick Hornby’s line in Fever Pitch about the fear of dying mid-season, of leaving loose ends, has always stuck with me for some reason.

“It’s all nonsense, of course, and football fans contemplating their own mortality know it is nonsense … The whole point about death, metaphorically speaking, is that it is almost bound to occur before the major trophies are awarded.”

And yet, as the final whistle blew that Saturday, there was some comfort to be found. Dad had arrived in the palliative ward on Wednesday after a trip between hospitals we were warned he might not survive. We’re pretty sure this will be his last Blades game. And he’s going out on a win.

Saturday 2 April, Stoke (A)

I always wondered if Dad saw a bit of himself in Tony Currie. He certainly shared some characteristics with his childhood hero – the long hair (in his youth at least), the charisma, the knack of being the centre of attention. Add it to the list of questions never asked, I suppose. He did play against Currie once though, in a charity match for De La Salle against an All Stars team full of ex pros from Sheffield and beyond.

After the game I was handed the hallowed Lane Lineup binder – a family heirloom containing every programme from the 1970-71 promotion season – and told to get the All Stars to sign it. I couldn't. After what seemed like a month (but was probably only 15 minutes) stood outside the All Stars changing room, Dad emerged, rolled his eyes and swung the door open. "Ey up lads, would you mind signing this for my young'un …" At least I assume he said something along those lines – I was slightly thrown by the sight of a buck-naked Emlyn Hughes.

If you wanted a snapshot of the difference between me and my dad, you might struggle to find one better. The timid son scared to knock on a door. The father happy to walk straight through it, regardless of what former England captains au naturel he might find on the other side. Dad could walk into a pub anywhere in the world and come out a couple of hours later having made a friend or gained a story to tell. Give me an empty bar and a book to bury myself in.

Those differences didn’t always make our relationship the easiest, but when it came to United we were rarely far apart. Perhaps the most vivid memories of my childhood are early Saturday evenings through the winter, when Dad, still playing for the village team in those days, would come in from the pub (the post-match debrief, of course, requiring a healthy intake of Pedigree), and open the door to the living room where I’d be ready: a collective groan if we’d lost, a what-might-have-been sigh if we’d drawn, and roars of delight for a win. And, whatever the result, we’d hug, my face buried into a jumper pungent with that quintessential now all-but-extinct Pub Smell of stale smoke and cask ale.

***

"Bad result yesterday, eh Dad?"

What I’d give for one of those hugs today. Three days prior, after what must have been a heartbreakingly painful talk with my mum, Dad had opted to stop his medication. That he has made it to this point is remarkable but after two weeks of palliative plateau the descent has started. This time there's no flicker of emotion when I arrive in the ward to tell Dad the score from the Bet365 Stadium and we know the end is near.

Tuesday 5 April 2022, QPR (H)

On Sunday my brother and I ponder bringing a laptop into the ward and watching the match with Dad. By Tuesday morning it's clear he's too far gone. Neither one of us wants to admit it, so we foist some of the blame onto what we imagine to be unreliable hospital Wifi. And my laptop’s knackered as well. We’d be disturbing other patients. We should let him rest.

Instead we watch the game together at mum and dad’s house and I spend the second half increasingly furious about the equaliser we’re about to concede but never do. I was going to blame this on hereditary pessimism but I don’t think that’s fair. I think Dad’s gift in that regard was a kind of Bladescentric fatalism, that sense of “Typical United” that needs no explanation.

It was there at the 1997 play-off final, Dad with his face painted red and white, my younger brother and cousin too, Uncle Rich his entire torso. (I was 16 and didn’t get my face painted because, y’know, I was 16). A wonderful day. A last-minute loss. “Typical United.”

Segers? “Typical United.” Unsworth? “Typical United.” Two semi-finals then 3-0 down after half an hour in Cardiff? “Typical United.” Take your pick from a litany of failures glorious and dismal across the best part of seven decades, no matter how unlikely, no matter how common-or-garden, no matter how comical or painful. “Typical United.”

We unanimously decide as a family that if the Blades make the playoffs this time around then they’ll probably win them. Finally the spiteful fates have decreed, after all that disappointment, after Palace and Wolves and Burnley and Huddersfield, not to mention Sunderland and Swindon and, for the love of all that is holy, bloody Yeovil for chrissakes, that this time, with Peter Ashdown now safely shuffled off this mortal coil, there will be no Elliott, there will be no Hopkin, there will be no Simonsen, and the universe will at last allow Sheffield United to win promotion through the playoffs.

“Typical United,” we agree.

By the time I get to the hospital on Wednesday, we know the end will come either today, tomorrow or Friday. I can’t remember if I told him the score or not.

On Thursday 7 April at just after 4pm, my dad, Peter Ashdown, died. He did go out on a win after all.

Saturday 15 April, Reading (H)

My branch of the Ashdown clan moved down to a village outside Derby when I was five. Dad’s heart always stayed in Sheffield but it meant matchday began with the drive up the motorway, followed by what was known to all of us as “The Manoeuvre”. This involved Dad jamming the nose of whichever family car it was at the time into one of any number of busy pre-match Sheffield intersections and then reversing into a parking space that had somehow gone unnoticed by other, less savvy, road users (To anyone else who’s been trying to park round Healey City Farm on matchdays over the past thirty-five years I can only apologise.) They’d end with Praise or Grumble spluttering out of range somewhere on the M1 southbound just after Chesterfield.

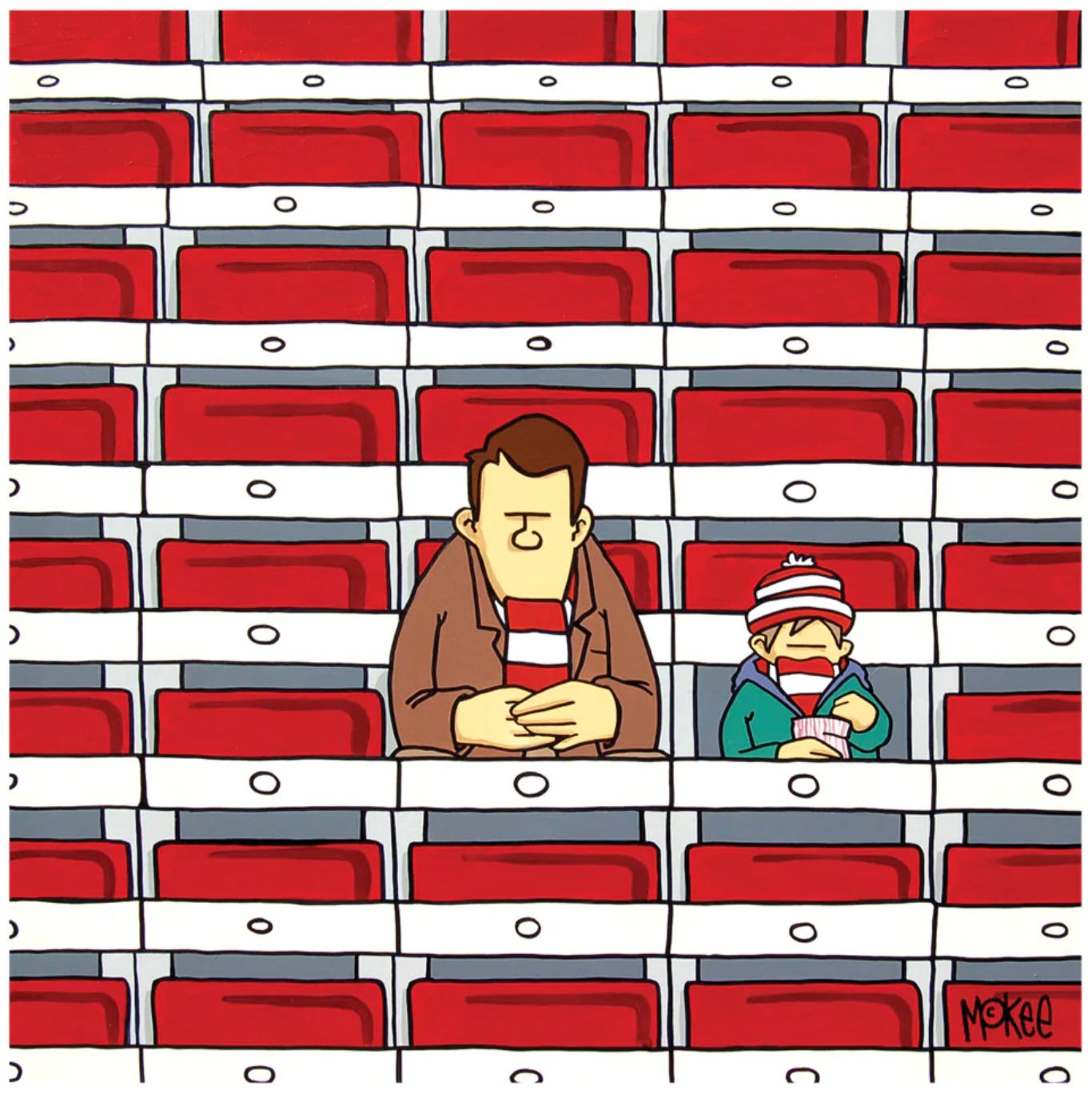

So my first trip to Bramall Lane without him isn’t typical. I take my nephew, Dad’s grandson, up on the train and wander towards the Lane from the station. I expect it to hit me as we first see the ground. I’m braced for going through the turnstiles to spark a jolt of sadness. I’m prepared for Annie’s Song to turn me into a blubbering wreck.

But I’m … fine (well aside from United grabbing a draw from the jaws of defeat and then a defeat from the jaws of a draw: “Typical United,” of course). In fact, there’s a kind of comfort in being in a place where we’ve shared so many memories down the years. And I try my best to instil a ah-well-you-can’t-win-’em-all breeziness to the train ride home.

It’s the last leg of the journey home that brings the suckerpunch. Grief is an odd beast, cowering in a corner just when you expect the claws to come out then bursting from its hiding place at unfathomable times, teeth clenched around your jugular. A couple of miles from home, now in the car, we turn into the long lane that leads to the village. It’s the only part of the journey that I would’ve done with my dad, time and time again over thirty-five years. Nearly time to get home and switch on my Sega Mega Drive. Or, as I got older, nearly time to get home, then get out again to meet my mates. Or, older still, to get home then join my Dad and his mates down the pub, seeing how many pints we could sneak in before we really were going to get in trouble with my mum …

It's there that grief is lurking in the hedgerows. And I realise: I’ll miss my dad at Bramall Lane. I’ll miss the chuntering. I’ll miss his flat cap and the lucky gloves and the lucky mints. I’ll miss him saying “Let’s nick one before half-time” a few seconds before half-time every single game. But the time we got to spend together I’ll miss more.

Friday 29 April 2022, QPR (A)

The funeral went well, or as well as these things go. The Manoeuvre got a mention in the eulogy, Dad’s mates all wore black Sheffield United ties from the club shop, Annie’s Song played as we filtered out into the sunshine. There’s a Blades crest on the front of the order of service. Dad would’ve loved it. United might have given him some grief over the years, but he really, genuinely, despite all evidence to the contrary, thought being a Blade was brilliant. I'm not sure he ever fully convinced me but who knows, maybe he was right.

That evening my brother and I drown our sorrows at his house as we watch United blow their playoff chances in the first half at Loftus Road. “Typical United.” Dad would’ve been shaking his head at the stunning, storming second-half comeback. “We never do it the easy way, do we?”

I stagger home, the order of service still in my inside pocket. On the back, Dad is on a beach somewhere, holding up his Sheffield United towel and beaming with pride.

John Ashdown is a Guardian sport journalist of nearly 20 years and Blade long before that. Used to have Neil Warnock’s phone number. Doesn’t anymore but Neil never answered anyway.

Incredibly poignant John. It's wonderful how such stories can be so moving because of the shared interest despite not knowing the subjects.

What a wonderful, honest and poignantly human account of life, and as a Blade, thanks for sharing, John. ⚔️