William ‘Fatty’ Foulke – A Dawley Mon

Gareth Thomas chronicles the humble beginnings of fellow Salopian and larger-than-life goalkeeping legend, William Foulke

Words: Gareth Thomas

Much has been documented about William Foulke’s time in the game and the success and growth he enjoyed whilst playing for Sheffield United Football Club. However, for this piece, I want to talk about the early part of his life and his first season of being a custodian for the Blades.

A Dawley Mon

Dawley is a town in Shropshire, first mentioned in the Domesday Book of 1086. It is the town I lived in for the first twenty-five years of my life. And it also happens to be the birthplace of the legendary Blades goalkeeper William ‘Fatty’ Foulke (whilst Foulke was the preferred method of spelling used by William throughout his life, his surname was sometimes spelt as Foulk, Faulks, Fowkes, Foulkes, and Ffoulk).

William Henry Foulke was born in Dawley, a coal mining town for over three centuries, on Sunday 12th, April 1874. His birth certificate is, in some respects, just as confusing as the spelling of his surname. The address given for the birth of William is Old Park, Dawley, but the column for the father was left blank. Meanwhile, William’s mother was Mary Ann Foulk but it appears that she signed her name simply as an ‘X’ on the birth certificate.

This mythical footballing character arrived on the earth twenty-six years after the birth and nine years before the death of another famous ‘Dawley Mon’, Captain Matthew Webb. Webb was the first person to swim the English Channel, a feat he accomplished in 1875, and he lost his life on 24th July 1883 whilst trying to swim through the whirlpool rapids on the Niagara River below Canada’s Niagara Falls.

Before I go any further, I should explain what I mean by describing these two very different but equally historical figures as a ‘Dawley Mon’.

Not so much today, but for many years, the people of Dawley conversed by using their own unique dialect. For example, “Bistna gonna do that, Bist” would be used instead of “you’re not going to do that are you”. Another example is ‘Mairt’ being used as the word for friend. Meanwhile, the word ‘mon’ would be used instead of man. Therefore, the term a ‘Dawley Mon’ means, quite simply, a Dawley Man.

Growing up

William did not live in Dawley for long; by the time of the 1881 census, he was living in the village of Blackwell, Derbyshire. At seven years old, he was the youngest of nine living at 122 Primrose Hill. He was one part of a household headed by his grandparents, James and Jane Faulks, their three sons James, Noah, and Alfred, as well as William’s older brother, Thomas. Meanwhile, the brace of boarders included Thomas Cadman and John Perrey, both natives of Shropshire.

All the men in the house were coalminers, plying their trade at the pit in Blackwell, whilst the boys – William and Thomas – attended the Colliery School, erected in 1876 by the Hucknall and Blackwell Company for the children of coalminers to receive an education.

William turned thirteen in 1887, and in November of that year, he reached the end of his formal education. Upon doing so he followed in the footsteps of his brother Thomas and all other male relatives and began working at the pit. It’s hard to even imagine how a boy of thirteen might fare working in the dark and dangerous environment of a coal pit, where the collapsing shafts, suffocation, gas poisoning, explosions and a whole host of other dangers were a daily occurrence.

A way out

Sport, in particular football and cricket, was an essential part of social life in the late 1800s. Indeed, from his window at 122 Primrose Hill, a young William Foulke would have been able to see the wall that encircled the village cricket pitch. A short walk would have taken him to the white lines and goalposts of the three local football pitches.

Such was the opportunity to partake in football and cricket that over the years, several sons of Blackwell went on to prosper in both sporting disciplines. Jimmy Simmons, who was related to William, would go on to play for Sheffield United in the FA Cup Final. Others who played football professionally included Terry Adlington (Derby County), Don Harper (Chesterfield), and Ryan Williams (Chesterfield, Hull City, and Bristol Rovers). Meanwhile, Elijah Carrington was a right-handed batter who played county cricket for Derbyshire – something that William accomplished too.

The village also had its own football team, Blackwell Miners Welfare FC. The club was founded in 1890 but sadly dissolved at the culmination of the 2011/12 season. But it was at Blackwell Miners Welfare that sixteen-year-old local coal miner, William Foulke, took up his position between the sticks.

A new posting

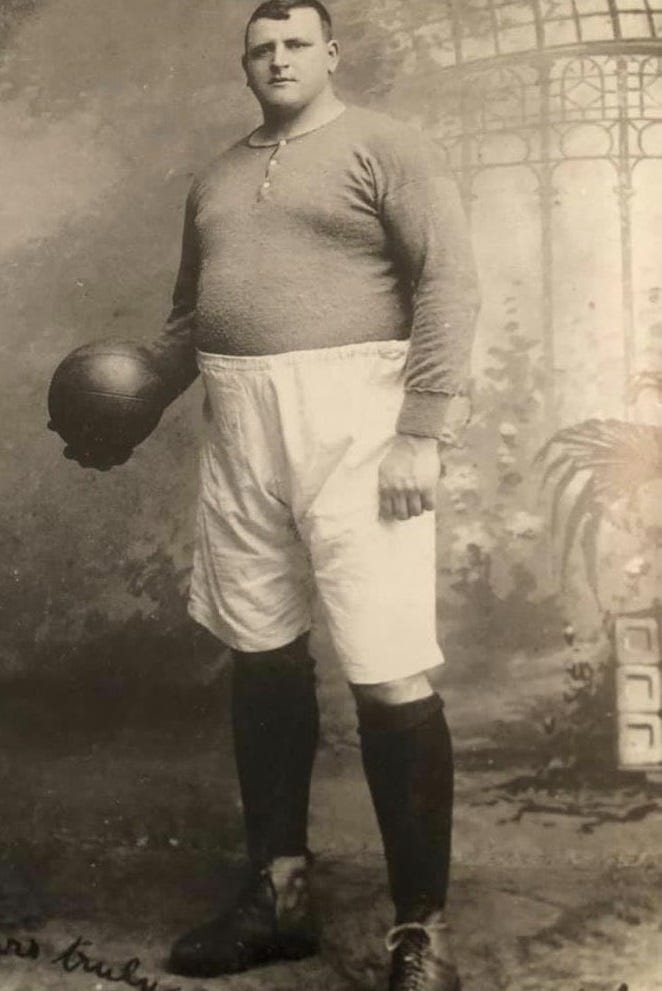

Foulke soon gained a reputation for being a goalkeeper who possessed an amazing talent to play in a position which is widely regarded as the most difficult to excel in. The 1892/93 season saw Blackwell demolishing most teams in the Derbyshire League, with a record of 114 goals scored and only 29 conceded. And that +85 goal difference was, in no small part, due to the performances of William Foulke, then described as a tall, slim figure, possessing the agility to comfortably save low shots.

Such was the success of Blackwell Miners Welfare FC that the club was considered to be of a good enough standard to take on a Derby County XI in a friendly. Friendly or not, Derby took no unnecessary risks against their lower-ranked opponents. Included in their XI was the great John Goodall, who, by the end of his career, scored 12 goals in 14 games for England. The result of the game remains a mystery but according to William’s obituary, it appears he made an impression.

He was not to be overawed. William handled the occasion remarkably, producing some fine saves. However, it was a flash point between him and John Goodall that made the headlines. A cross was sent into the Blackwell box. Goodall rose to meet the ball with his head. But as fast as lightning, William left his goal line and jumped to punch the ball to safety. And in doing so, connected with Goodall with so much force that the striker lost a few teeth. William’s performance caught the attention not only of reporters and local newspapers but football folk up and down the land.

His qualities began to garner increasingly glowing column inches, and following the 1892/93 campaign, there were three First Division clubs showing a keen interest in acquiring his service. Nottingham Forest and Derby County were keen admirers, but quickest to the mark were Sheffield United. The Blades wasted little time in talking to the player and his employer, Blackwell Colliery.

At the end of the negotiations, Sheffield United put forward an offer that was too good to refuse by both parties. Blackwell Colliery would receive £20. William would receive £5, which was huge money for a young footballer in the formative years of his career. To put the sums of money into some context, £5 back in 1894 is worth approximately £503 today. Both the colliery and William agreed to the terms and the deal was done.

Later during his time at Bramall Lane, William would receive £3 a week with bonuses of 50p for an away win, 25p for a home win, and a £1 bonus for any victory over Sheffield Wednesday. Fantastic money for the time, and what is certain, considerably more than he would have earnt working down the pit.

Sheffield United

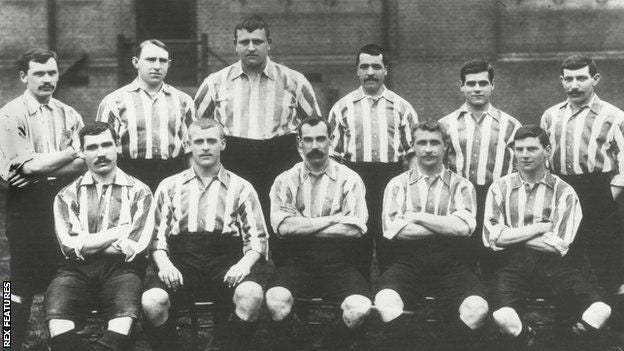

William made his debut for Sheffield United on Saturday 1st September 1894 at home against West Bromwich Albion. The game ended in a 2-1 victory for the hosts, and a report in the Sheffield Independent described William as ‘United’s new, tall, cool goalkeeper’.

The Blades’ new custodian followed his debut with his first clean sheet in a 4-0 victory over Wolverhampton Wanderers at Molineux. In his third appearance, he was to taste defeat for the first time when Preston North End beat United 2-1. However, he still received excellent reviews in the press for his performance, as he did when Sheffield United met Sheffield Wednesday at Olive Grove, on Saturday 27th October 1894. The game resulted in a 2-1 triumph for United, with the Sheffield Independent stating:

Foulke’s superiority to the Wednesday custodian was the main factor in the success of his team.

That win over Wednesday was followed by a winless run of six games. Over the course of the season, the Blades enjoyed mixed fortunes, but whatever the result, Foulke found himself spotlighted. A young man who had climbed out of the pit and into a Sheffield United team who would finish in sixth place in his first season. A footballer whose success grew in proportion to his stature: one First Division title, one England cap, two FA Cups, and twenty-four stone. He became a maverick, a folk figure, and a Sheffield United legend – but he started out life as a Dawley Mon.

Shropshire-based Gareth Thomas is a former goalkeeper himself, and a perpetual lover of the beautiful game. He can be found writing about a plethora of football-related matters on his blog Gareth's Football Travels and working as volunteer media officer for Anguilla Football League side Uprising FC.

My favourite Foulke quote, from the 1901 FA Cup semi-final victory over Aston Villa: "When the interval was called the Villa were dodging about in front of Foulke, who moved his ponderous bulk with the celerity of an eel."

Thank you, Gareth

Quite amazing the number of (famous) Blackwell men who went into sport and the coalmine’s loss was certainly football’s gain. Foulkes was obviously a ‘born’ goalkeeper – being a great stopper whether a “tall, slim figure, possessing the agility to comfortably save low shots” or the heavyweight he was later to become.

There’s obviously something in the water at Dawley in producing all these sportsmen, particularly Foulkes, and well done to Sheffield United to hanging on to him, despite having to make a “record” payout and then pay “high” wages.

It’s also interesting that the same teams were around then – Wolves, Preston, Derby, Wednesday, etc. All the older teams still in the running today.

Another fascinating piece in the Sheffield United history jigsaw!

Sue.