The Chris Wilder Myth

Sheffield United Football Club cannot rely on a proven manager without reflecting on the recruitment that brought us success.

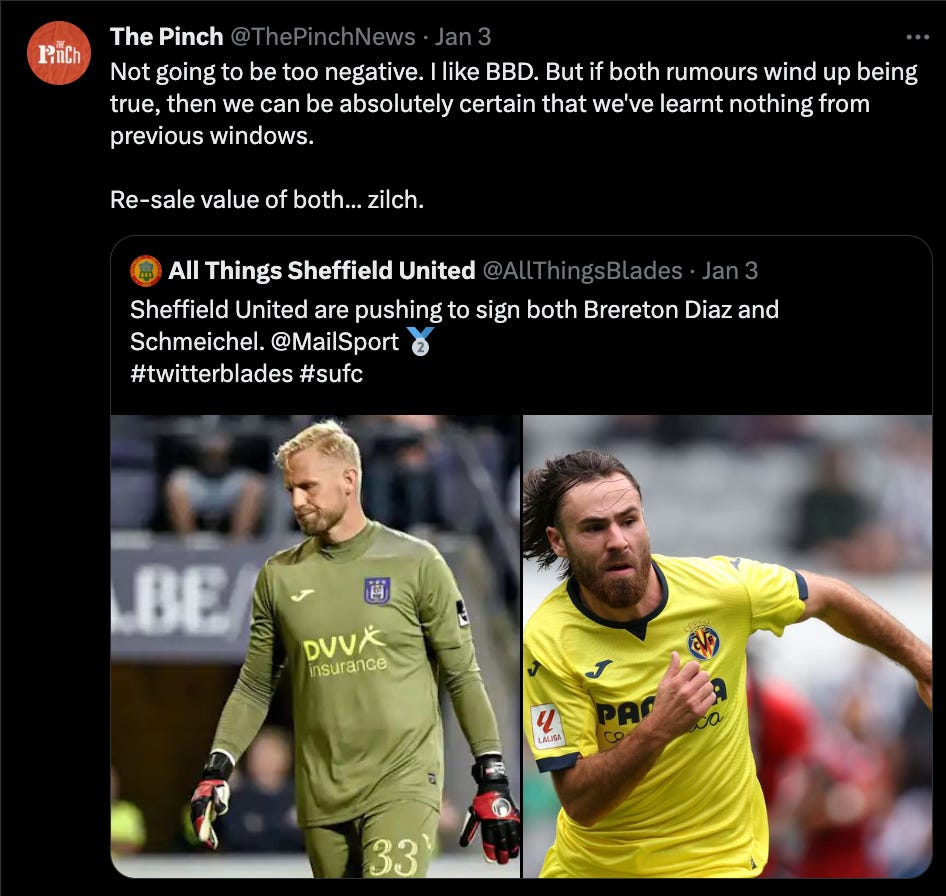

Earlier this week I hit 'send' on a Tweet from The Pinch account, rather than my personal one. Such are the trials and tribulations of having multiple accounts on several devices. Little did I know that it would drag me down a rabbit hole that would wind up in a discussion about “The Chris Wilder Myth”.

I took some flak for the post. Nothing bad-mannered, just fans pointing out that any nascent deal for Ben Brereton Díaz or Kasper Schmeichel would be a loan, and therefore any discussion of re-sale value was missing the point. It's a fair argument.

The underlying logic of that tweet was this: why does Sheffield United Football Club ignore its own hard-won success? And, given the success of Chris Wilder's recruitment from 2016-2020, why don’t we return to basic principles of finding value in our recruitment?

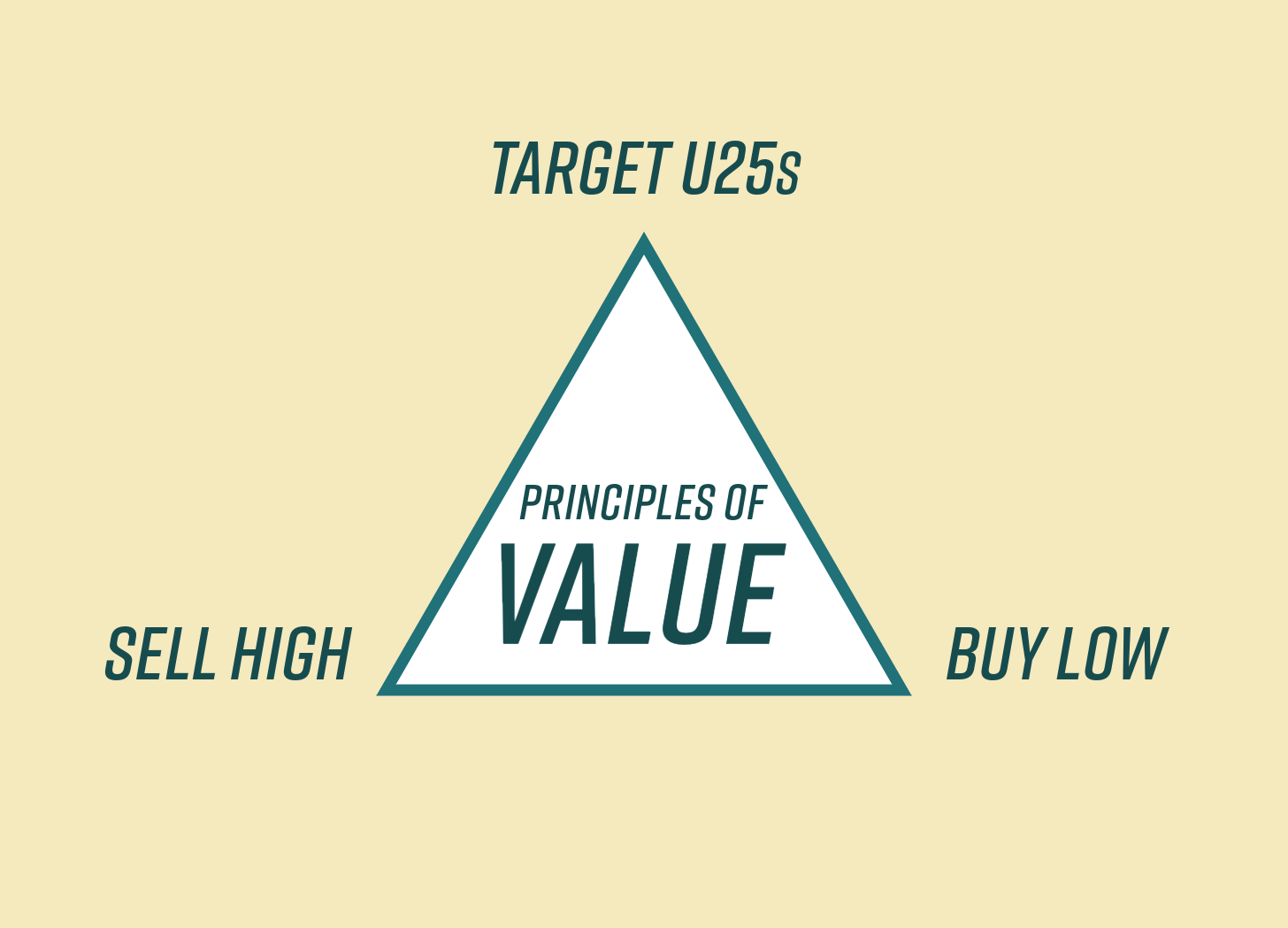

What were those principles?

Buy low

Target (mostly) players under 25 who can improve

Sell high (that is to say, create assets, not deadwood)

In 2016/17, Sheffield United remained a big fish in the League One pond. We could, to a certain extent, hook the brightest and best relative to our position. John Fleck is perhaps the most pointed example (already a known talent). But we also added Jack O'Connell and Mark Duffy in the summer, as well as Samir Carruthers in January, who at the time was a bright prospect. Fleck, O'Connell and Carruthers had one thing in common: if they could become shining stars of a team on the up, then any club wanting to buy them would have to pay more than we did. Whilst we didn’t sell any of those players “high”, for three consecutive seasons, we plausibly could have.

I’m not saying we were necessarily wedded to those principles in any conscious way. However, the facts show that our recruitment and those principles overlapped neatly. Especially between 2017/18 and the end of the 2018/19 season, when we bought George Baldock, Enda Stevens, John Lundstram, Lee Evans, Ryan Leonard, Nathan Thomas, Oliver Norwood, John Egan and Kean Bryan.

Subtract Bryan and Thomas from that list, and you are left with multiple players who were capable of plying their trade to a high level in the Championship, and some even in the top flight. Subtract Bryan and Thomas again, and all of them are playing in the Championship or higher today. That is value.

Of course, there were players over the age of 25 ( e.g. Mark Duffy, David McGoldrick, Leon Clarke, Jake Wright and others) who broke the “Target U25s” principle. None of them had any great re-sale value, breaking the “sell high principle”. Nevertheless, every signing in those years fell under the “buy low” principle, even Egan (circa £4m) and Norwood (circa £2.5m) fall into that bucket thanks to their quality.

All of the above is to say that Chris Wilder didn’t get Sheffield United promoted on his own. Success was rightfully his, but it was also down to the players who scored the goals and stopped the shots.

So, what happened next? Simple: we relied on the old guard — and why wouldn’t you? — and didn’t sign the players to score enough goals and stop enough shots.

Bottoming out via the top-flight

If I had to isolate one key criticism for recruitment in 19/20, it is this: we largely targeted the right age range but we bought way too high. And when you buy too high, you can’t sell higher — the value triumvirate implodes.

I don’t know what happened. I don’t know the logic of our dealings. But I suspect we were too ready to accept the inflation pressures of being a top-flight team; too eager to “buy high”. Moreover, it’s abundantly clear today that – for one reason or another – we opted against overseas targets.

The fees paid for our next batch of would-be value assets – Sander Berge, Oliver McBurnie, Callum Robinson, Ben Osborn, Lys Mousset, Oliver Burke, Jayden Bogle, Max Lowe and Aaron Ramsdale – total around £100m (according to TransferMarket). I've not even mentioned Luke Freeman there as he wasn't under 25, but his signing broke every one of the three principles.

It’s easy to stare at the car crash through the rear-view mirror. So I’m not going to criticise how or why our recruitment team identified these individuals as the players to sign. Instead, we should focus on the price.

Sander Berge was a great signing. Perhaps we overpaid a little, but if Sheffield United could've avoided relegation, and if his injuries didn't preclude quite so much game-time, we could've easily made a profit.

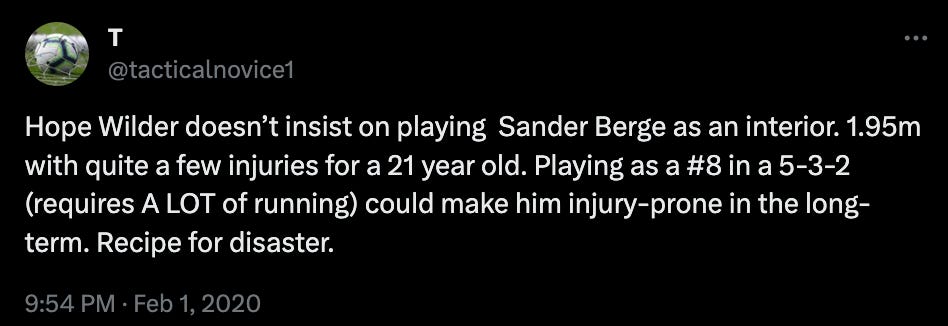

Digression: How we broke Sander Berge and killed his market price

When you make a club record signing, it's in your interest to protect your asset. Sander Berge arrived with a history of injuries. In February 2020, one Tweeter made an astonishingly prescient argument about the relationship between Berge's positioning and possible injury.

If one person on Twitter could identify that problem, it seems likely that a whole football club understood the facts too. Nevertheless, we all know what happened next: the injuries came, and our prize asset lost value.

But let's not dwell on the ifs and buts. Let's trade in reality.

The rest of the signings, to a man, represented poor value. Had Aaron Ramsdale continued to chuck the ball in the back of his net in the second half of the season, he wouldn’t have got a move to Arsenal. Because of known issues around his professionalism, Lys Mousset was always a risk and a hefty risk at more than £10m. Ben Osborn, a player who never sparkled in the Championship, cost more than Oliver Norwood(!). Oliver Burke… *sigh* Oliver Burke cost more than £5m.

Shorn of clear-minded principles of value, our recruitment was a minor disaster. Only one player signed in the top flight was sold for a profit and that was Ramsdale (and Iliman Ndiaye, signed by the academy). The rest are emblematic of our problems ever since; drifting, as we did, off the road to value and down into the hedgerows of value lost.

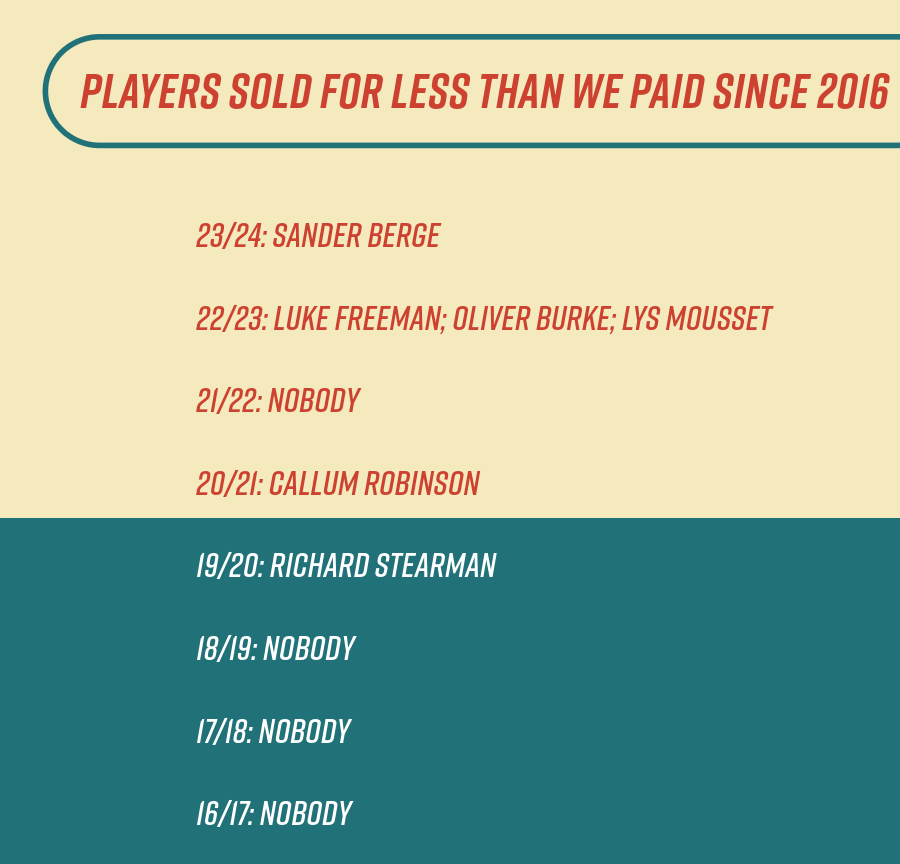

Losing value

Since relegation in 2021, Sheffield United have demonstrated an almost unique ability to lose value. Both losing players with a potential market value on free transfers and also player performances undermining their market value.

There have been players sold to avoid them leaving on a free. And there have been a clutch of players who have left on a free who would’ve demanded some kind of fee otherwise. Those include but are not limited to John Lundstram, Sander Berge, Iliman Ndiaye, Ben Whiteman and CJ Hamilton.

That’s nothing. The ugliest picture is painted by the list of players we’ve sold for a loss before and after January 2020.

Now let's look at players we have sold for a profit since 2016:

The politics behind the transfers is not the point of this piece. I only want to point out the scary question that comes next. Between now and summer, who are the players might we sell for profit, who for a loss and who leaves on a free?

I’d argue the only player we could sell for value is Anel Ahmedhodžić (with a few of the kids making up the next spots). There is both a frightening number of contracts up for renewal and a worrying lack of long-term squad building.

For me, the cause of poor recruitment has been a miscalculation of what constitutes value. And poor recruitment is the handmaiden of medium-term decline. Yes, we are in the Premier League, but I challenge any fan to tell me with a straight face that we’ve deployed a serious recruitment plan for survival. We haven’t. We have failed to plan and thus, planned to fail. And the worst thing about it is that it need never have happened.

Why this matters now

Squads of players don’t decline overnight. The good business done in the years between 2016 and 2020 has endured to now. Players like Stevens (gone), Egan, Norwood and Baldock were the future once; that is no longer the case. We’ve failed to get ahead of the game, and now we need a major reboot. Revolution, as opposed to evolution, is a chaotic thing — and today, we’re in amongst the chaos.

The money spent this year under Heckingbottom, when set against the departures, has not done good work:

£15m for Hamer - (No complaints at all)

£10m for Souza - (Too much)

£5 for Trusty - (Too much)

£4 for Traoré - (Too much)

£1m for Slimane - (TBC)

A deal for Cameron Archer – an elite player in the Championship – which will result in his departure at the end of the season

Even when spending small sums, we’ve spent them relatively badly (see Traoré leaving in the next available window). We’ve built a first XI and a squad that is incapable of challenging for survival. Or rather, we’ve failed to build a squad. And even our worst expectations have already been met.

How can we compete with a backline so penetrable it would let peas through a sieve, with a goalkeeper who prevents us from keeping possession, with a striker who is more notable for his absence than his presence, with kids in the squad who should be out on loan in the lower rungs of the EFL, and with an owner who chooses to enrich a YouTuber who sang the praises of Dozy contrary to any modicum of critical logic?

And so all of our eggs fall into a familiar basket: Chris Wilder. It’s a good basket. But we cannot expect him to play magician again, not when we are short of the cash needed to even attempt the trick.

I will avoid saying I feel sorry for Wilder because he knew what he was entering into. Yes, he has improved performances from woeful to not good enough. Yes, after six games (and 0.66 points per game) we're on course for 21 points— an improvement, albeit 21 would be one fewer than our previous relegation. Yes, he has given us cause for optimism. But there’s still one considerable concern hanging about the place: not about him, but about recruitment.

Believe in Wilder, not the myth

Let’s not talk about Chris Wilder doing the impossible and keeping us up. We’d all love it, but the likelihood is close to zero.

We should talk about how Wilder has given us a tantalising glimpse of a manager refreshed. Willing to give youth a chance. Confident in changing shape and tactics. Adaptable to different situations. And perhaps most importantly for me, a happier, smilier, more positive Wilder.

Like in 2016/17 when Wilder took over, we have the skeleton of a quality starting XI for Championship level, and unlike 16/17, we have the massive boon of four or five young prospects who can bolster a squad.

But how do we recruit when relegation is an almost certainty? Do we (a) attempt to recruit for the short-term and try to stay up, or (b) attempt to add players who can make a tangible difference next season? Maybe you can do both. Maybe we have cash to spend. Maybe we don’t. I don’t know.

What I do know, is that short-term loans without options for permanent signings – like Ben Brereton Díaz and Kasper Schmeichel – are symptomatic of a total detachment from the principles of finding value. They will only support the medium-term and long-term future of this football club if they keep us up. And if they can’t, the gamble will have failed twice: not only a failure to stay in the top flight but a failure to plan for what comes next.

I know that many people don’t buy this assessment. They see it as preferable to sign short-term options, and if and when we’re relegated; that’s the time to revamp. I politely disagree, because we are not Burnley or Watford or Leicester. We can’t sign a whole new squad chockablock with talent, not with this owner.

In my view, the revamp should start this January. Because even if you believe that Wilder is a miracle worker — and in the footballing context, he has undoubtedly performed miraculously — he has no more ability to kick a ball or clear a cross than you or I.

Fervent believers in the Wilder mythology do him a disservice when they put faith in a January Transfer Window built neither on the principles of finding value nor on the foundations of his previous success. Instead, if reports of six-month loans are to be believed, we’re building our future on the verges and hedgerows of a slow-moving car crash that started in Summer 2020.

I don’t think it’s fair to put all our eggs in the Wilder basket, to place all emphasis on a theory of football as one of “great men doing great deeds”. That is the Chris Wilder myth: that he can succeed against a backdrop of chaos. Miracles in the Premier League are far scarcer than miracles in the Championship or League One. He needs good recruitment as much as good recruits need Chris Wilder. Football clubs need structure. Sheffield United desperately need a plan.

The only way to break out of this cycle of decline is to identify targets and sign players who can give you a competitive advantage over the long hot slog of a Championship season. The quickest route to success? Start with the tried and tested principles of finding value and take it from there. Sadly, with our owner looking to sell, our horizons appear smaller than Bénie Traoré. So believe in Wilder, but don’t believe the myth.

Thanks, Sam

Can’t argue with any of that.

“… drifting, as we did, off the road to value and down into the hedgerows of value lost.” . . . what a great summary.

“There is both a frightening number of contracts up for renewal and a worrying lack of long-term squad building.” . . . Nail. On. Head.

“Football clubs need structure” . . . I hate all this short-termism with players on loan for one or half a season, even though it’s become necessary. Yes, players join because we’re in the Premier League, but for how long? And if we get relegated you can bet they’ll be out before you can say knife, because the reverse of the medal is that we don’t have any money to offer them.

But keep the faith – ‘tis the Sheffield United way!

Sue.

Spot on. I think the biggest mistake of the summer was not buying Doyle. Albeit due to prevarication about loans and finance. but I think it would have been a good buy instead of good bye. (Sorry!)