Table Numbers: Sheffield United, the Premier League and the future

Does the table lie? How 'table numbers' contextualise Wilder vs Heckingbottom, season vs season, today vs tomorrow.

Sam Parry

It was not expectation but hope that led Prince Abdullah to appoint Chris Wilder — hope that he might improve a failing team; hope that he might accrue more points; hope that he might succeed on a shoestring, and hope that he might perform a miracle.

Hope has played little part in his inability to do so. Wilder signed up for the impossible task, shouldering a similar burden to the situation of his previous departure, where we simply cannot cope with the quality around us.

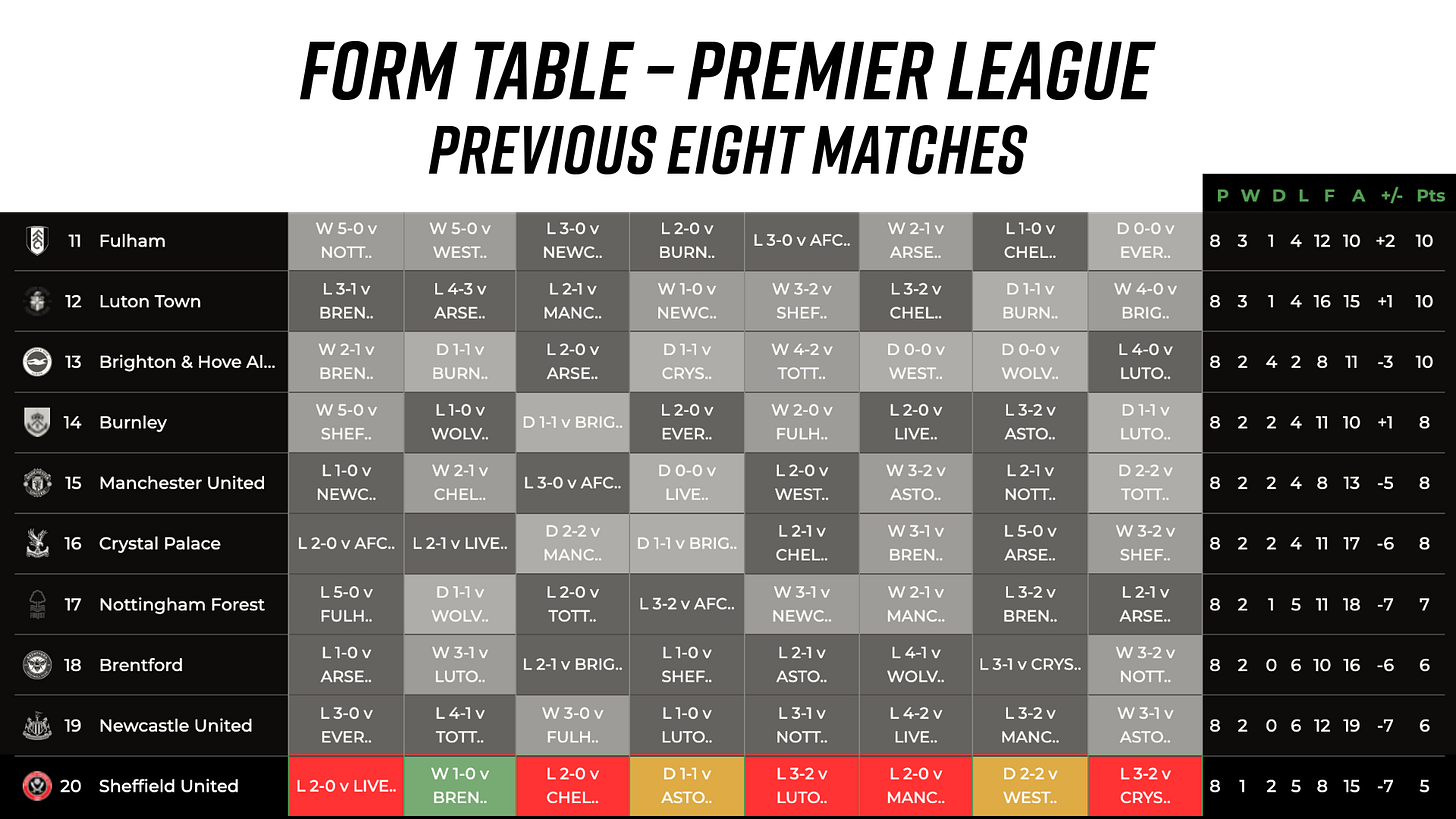

For his part, Chris Wilder has returned some semblance of positivity to Sheffield United Football Club by overseeing a rapid improvement on the pitch. And whilst our rejuvenation has not translated into the points required to stay up, it’s been an improvement that not only passes the eye test but correlates with United’s underlying numbers over the past eight games — so let’s have a look at ‘em.

To some extent, this table is lying — I’ll get to that. But first, let’s use ‘table numbers’ to compare Wilder and Paul Heckingbottom’s efforts, and then contrast it all with every other Premier League club’s efforts in the past.

Table Numbers

The seeds of our latest defeat to Crystal Palace were sewn in the summer when a transfer window of poor recruitment left us short on quality in all areas of the pitch. If the Blades had remained in the Championship, there’s little doubt that the implications of a poorer squad would see us finish below the 2nd-place we achieved last year. And the Premier League isn’t just a different kettle of fish, but an entire ocean — we’re lacking armbands and colourful, foam floaty things.

To analyse the effort we’ve made this year, I’m going to turn away (mostly) from those detailed stats often cast in code-like acronyms: SCA, PrgC, xAG and the like. Instead, I want to look at the metrics we’re all familiar with. You’ll know them well — the letters: P | W | L | GF | GA | GD | PTS.

The advantage of these is that their relevance to this season is reflected in the history of every Premier League season that has come before.

Played/Points

Between 2016 and 2023, the average number of points required for survival was 34.1. Put simply, if a team gets 35+ points they nearly always stay up. In fact, only four teams in the past eleven seasons have been relegated on 35 points or more, and only one in the past seven seasons (Burnley 21/22). That was our target; now, in all likelihood, it is utterly unreachable.

Under Paul Heckingbottom, we averaged 0.36 points per game (PPG), which over a 38-game season, would translate into 13 points. Under Wilder, our PPG is 0.63 and that averages out at 23. There’s a full 10-point gap from Heckingbottom to Wilder, but another 12-point gap, again, to reach the safety net.

Both managers this year are failing on results.

Goals For

Since the Premier League began, there has been a tight relationship between the number of goals a team scores and the number of points they accrue. On average, if a team scores just one goal per game it equates to an average of 1.03 points per match — 38+ is enough to stay up.

Under Paul Heckingbottom, we averaged 0.79 goals per game, whilst under Wilder so far, it is 1.00 on the nose.

Chris Wilder has done a good job on goals scored; Heckingbottom less so

Back in 19/20, when Chris Wilder delivered a 9th-placed finish in the top-flight, we only scored 39 goals (1.02 per game). But we made those goals count: of the 14 games we won, 7 were 1-0 victories and 9 were won by a margin of a single goal.

There are two things to learn from this. The first is that Chris Wilder can set up teams that average around one goal per game — a safety net requirement. But the second is, that when you only average a goal a game, you can’t afford to concede many. It’s something Wilder struggled with in 20/21, where low-margin affairs went against us. And the record this season makes for grim reading.

Goals Against

Teams conceding fewer than 61 goals in a season tend to stay up — only 7 in 30 relegated teams have conceded fewer and gone down over the past ten years.

Under Paul Heckingbottom, we conceded an average of 2.79 goals per90, whilst under Wilder that figure is 1.88.

Heckingbottom’s record is pure relegation form and that’s no surprise; Wilder’s is also relegation form but (as I’ll discuss in a second) it’s somewhat unlucky too.

Goal Difference

One of the most notable dividing lines between top-half clubs from bottom-half clubs in the Premier League this season — other than league position — is the stark contrast in goal difference. Every top-half club (bar Man United) has a positive goal difference, whilst every bottom-half club has a negative goal difference.

Ours stands at -35, the poorest record in the league.

Expected Goals & Expected Goals Against

Clearly, our record is one of a poor team deserving of its lowly league position. But have our performances been better than our results? Over the campaign so far, is there anything to suggest we have we been unlucky?

Expected Goals (xG) is a metric for measuring the likelihood that a shot from anywhere on the pitch goes in, with 0.00 being impossible and 1.00 being guaranteed. Now, nothing is impossible nor guaranteed in football, so you’ll rarely see a shot given 0.99 xG. A penalty kick, for example, is only 0.76.

This metric is useful. If a team’s Goals For column shows a stark difference from its Expected Goals column, we might discern that a club is either very good at finishing low-quality opportunities or very bad at finishing high-quality opportunities.

Under Paul Heckingbottom, our per-game average looked like this:

GF (0.79) | xG (0.78) | GA (2.79) | xGA (2.21)

Under Chris Wilder, our per-game average looks like this:

GF (1.00) | xG (1.10) | GA (1.88) | xGA (1.56)

Whilst we might have underperformed our xGA when Paul Heckingbottom was in charge by a pretty substantial 0.58 goals per game — that’s the equivalent of 22 goals over a season — I don’t think anybody would argue that we were unlucky.

In contrast, and what is most encouraging for the future, is how dramatically our xG has improved in all directions since Wilder arrived. We’re scoring a goal a game. We’re deserving to score a goal a game. We’re conceding 1.88 per game, but a few of those — hello Olise (0.03 xG), hello Eze (0.63 xG, 0.03 xG) — are, frankly, ridiculous efforts that rarely hit the back of the net.

So, if we could reduce the GA column to the same as the xGA column, Wilder’s team would concede 59 goals over a season, and that’s a safety net requirement. All good signs. But — and there is a but — we’re already too far gone to survive this season.

Did it need to be this way, and what next?

Ever since the Premier League changed to a 38-game season, less than half of newly-promoted clubs — just 43% — have been relegated in their first season in the top flight. Let us never imagine that our predicament was unavoidable.

Had we kept players like Sander Berge and Iliman Ndiaye, the early part of the season would not have been such a hot mess and we’d have retained the special talents of players who can sprinkle their magic in games, and create goals from nothing. We have too few of those players now, and we’ll be losing bodies in summer — a lot of bodies.

Chris Wilder has stated publicly that he’ll only offer new contracts to “two or three” players. And given the number of contracts expiring and loans coming to an end, that will leave us amidst a full-blown summer rehaul.

CONTRACTS/LOANS EXPIRING: Adam Davies, Ben Brereton Díaz, Ben Osborn, Cameron Archer, Chris Basham, Daniel Jebbison, George Baldock, Ismaila Coulibaly, James McAtee, Jayden Bogle, John Egan, John Fleck, Jordan Amissah, Max Lowe, Oli McBurnie, Oliver Norwood, Rhys Norrington-Davies, Wes Foderingham, Yasser Larouci.

Perhaps that’s a good thing. There’s logic to that argument. However, after the summer we endured in 2023 — with late business, bad business and terrible business — it’s hard to trust the process.

The situation at the top end of the pitch is a case in point. Cameron Archer must be bought back by Aston Villa upon our relegation. The contracts of McBurnie and Jebbison are expiring, James McAtee will return to Man City, and Ben Brereton Díaz is doing an excellent job of putting himself in the shop window to be bought by someone (probably not us).

That leaves Will Osula and Rhian Brewster as the only strikers guaranteed to be in our squad next season. Brewster has scored 4 goals in 65 league appearances. Osula — full of promise no doubt — has scored 0 goals in 20 league appearances. Those records do not fill me with confidence.

I hate saying it, but all we are left with is hope. The same hope that went into hiring Chris Wilder and asking him to perform the impossible. To me, the short and medium-term future looks pretty treacherous. We need firmer footing to seize on the very real opportunity to bounce back next year. But even if we perform well, even if we secure good results, we still might not.

We know how tough the Championship is. We can start to see already who our rivals might be. And my biggest hope, my best hope, the thing I am most confident about is Chris Wilder. Because, in theory, he gives us a much better chance than Bryan Robson all those years ago, and Slavsa Jokanovic just three years ago. The first eight games of his second spell tell us he is back, and he’s not messing around.

However, in pinning our hopes on the Wilder Mast, we are embarking on a very risky but potentially rewarding voyage. Risky, because we could end up sinking if things get rocky and he leaves. Rewarding, because at his best, he remains one of the most effective managers in the country, easily capable of another Championship promotion.

I’m pretty sure Chris Wilder will find a way to get a tune out of whatever squad he builds over the summer, but the ensemble is only as good as its instruments. If we end up with cereal box guitars and tin can drums, then the blame lies not only at the door of the ownership but the manager. He described a “united front” between manager and owner, but from my vantage point, I have yet to see more than managed decline.