Steve, or the story of how The Pinch came to be

Popes and Panzers, war and Wednesday — Steve’s remarkable life ends in the places we know: football terraces, barbershops and home. But it begins in a world we can barely imagine.

WRITTEN BY SAM PARRY

Bear with me; this is the story of how The Pinch came to be. It’s much more than that, of course. The second, third and fourth-hand telling of a few moments in a life. I’ve always wanted to write this story down. Hopefully, I can do Steve, a man I never met, justice. Because what a life…

Redmires or Lodge Moor

A concrete oblong rises above the mud. There are a lot of leaves. The odd footprint. Scraggy saplings fighting for light beneath the canopy up at Lodge Moor or is it Redmires?

The woods are damp and dark. They smell like woods. That mulch of decay and new growth. But there are signs of another life.

In one direction lies brickwork, only a foot or so high, framing twigs, weeds and dirt. It all feels like a draughtsman’s sketch. You can see where a door might once have stood; a window, a wall, a corridor. A village abandoned before it was ever built. But it was built, and there were people.

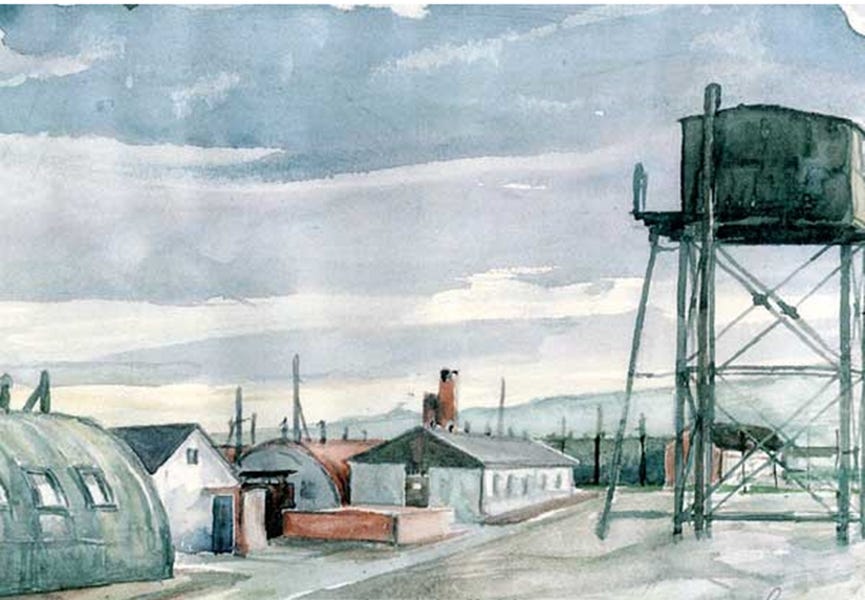

In the early part of the 20th century, the canopy was cut away and replaced with corrugated iron, wooden frames, hulking girders, giant fences, great big water tanks, and, everywhere, sharp metal edges. As many as 11,000 people once lived here, in Camp 17 at Lodge Moor Prisoner of War Camp. One of them was Steve.

Becoming an alien

During the Second World War, life in the camp was harsh and often dangerous. Its population was a patchwork of Germans, Ukrainians and Italians — all classified as enemy soldiers, though within that simple categorisation existed deep contrasts of belief, background and human aspiration.

In 1945, a group of pro-Nazi soldiers plotted an escape by tunnel. A non-Nazi prisoner learnt of the plan and warned the British authorities. He was rounded upon by the plotters and killed — a single brutal kick to the head.

The brutality of prisons is never hard to find. Yet in such places, there is always also hope, art, and kindness. Heinz Georg Lutz, an architect and painter, made linocut prints of Camp 17 using found materials and ink. Those prints survive to this day. There were other skilled people, too. That’s not so surprising. There were thousands of people, and Steve’s skill wasn’t cultivated in Sheffield but almost 2,000 miles away on the margins of Europe.

As a child, Steve had cut the hair of friends and family in his village, the same village that Russian troops had later sacked and burnt. It was that destruction which led him to fight against one side and for another. Decisions made in moments when the world is burning are never simple. His brothers made different choices — one fought with the Russians, another with independent fighters.

Steve ended up crewing German tanks before his capture. When he was brought to Britain and imprisoned at Lodge Moor, he returned to the skill he had learned in his youth: he cut hair for the other inmates.

The British soldiers who ran the camp, like those they guarded, held no uniform view of the world. Some were cruel. Others were not. Some held resentment; others sympathy.

On occasion, prisoners were granted leave for short trips outside the camp fences. One day, Steve and fellow internees were offered tickets to watch Sheffield Wednesday Football Club. Escorted by truck, around fifty prisoners were taken to Hillsborough. They watched Wednesday win 3–1. After the game, local supporters — many of them serving officers — plied the uniformed prisoners with cigarettes and chocolates. Given that kindness, you can’t blame Steve for the allegiance that came later. But before his footballing affinity was allowed to flourish, Steve would become an alien.

Alien

When Steve left the POW camp, the British government classified him as an alien. Each year, he had to report to the local police station for a stamp. He found work first in the steelworks and then at Silica Bricks in Stocksbridge. He met May, a land girl from Sheffield, in Retford, whom he would later marry.

It was May who encouraged him to return to his childhood pursuit — and his wartime trade — of cutting hair. They saw an advertisement for a barber’s position at a local shop. May arranged the interview. When Steve turned up, the manager turned out to be a fellow veteran. He tested Steve’s skills, liked what he saw, and gave him the job. Steve would remain a barber for the rest of his life.

When Teddy Boy hairstyles began to take hold, Steve travelled to London to learn how to cut the best DAs. He took a chair first at Tom’s and later at Fantham’s, the salon owned by former Sheffield Wednesday player Johnny Fantham. This is where he made a name for himself. If you were a footballer in Sheffield at that time, chances are, you asked for Steve. And if you weren’t a footballer, chances are you wanted to hear the tales of the footballers who passed through. There were plenty of those. And plenty of those remembered him.

The Barber

Here is a selection of memories posted about Steve on various chatrooms and forums.

Of the seven barbers I remember the Orio brothers, Arthur Holmes, and of course Steve, and I think his name was Bdjala, and he was the top stylist, always plenty “Waiting” for Steve and the latest styles, the D A for one.

Think it was called Johnny Fanthams or summat like. Two English fellas and a big foreign fella, East or Central European guy called ‘Steve’. Never lost his foreign accent but was always good for a laugh and a story while you had you had your hair cut....When John Fantham opened his salon on Division St... Steve went with him and so did I.

Isn’t that the place where Steve was, the guy who used to crew panzer tanks during our little disagreement with Germany?

...his accent suggested that he had been born in Poland, and he was the Pope’s (John Paul II) double to look at. In fact he used to have a picture of the Pope on the wall, just to take the mickey out of himself - he had a good sense of humour.

I was told that Steve was a guy that fought with the Germans during the war and was a POW from the Lodge Moor camp who stayed here rather than returning home...Anybody know the truth of the matter?

Steve was Ukrainian so it would have been difficult for him to return home having volunteered for the Waffen SS to fight the Russians.

I think his name was Stefan Bajdala...In about 1994 his sister came over from the Ukraine to visit - it was quite an emotional reunion.

Steve was (and I hope is) Ukrainian.

The face and the faces

Steve was Ukrainian. Although the village he grew up in was right on the border of Poland and Ukraine – walking distance, in fact. And that world would catch up with him again as he settled into a new life in Sheffield.

One day, a man sat down in Steve’s chair. He sounded foreign, like Steve. Steve asked how he wanted his hair cut. The man smiled and said:

“Stefan, the same as you cut it when we were kids.”

The man was from the same village as Steve. That remote village on the border. His name was Ivan ‘John Comic’ Chomik and he lived up to that billing. Ivan worked on the railways where, what wasn’t nailed down, came free. After the Sunday evenings they spent together, Steve would drive home not only with big dinner sitting heavy in his stomach but a tank of petrol fuller than it had been on the drive there. John was a character but not the only one.

From Derek Dooley and Joe Shaw all the way to Neil Warnock, the faces had their hair cut by Steve. There was one exception, or a number of exceptions. When the fashion for long hair arrived, embodied by locks of one Tony Currie, Steve was not happy about it. But fashions changed.

Steve changed with them. But the jokes remained the same. He’d ask customers if they were Wednesday or United as he leant them back in their chair, cut throat razor at their neck. This wasn’t enough to stop the letterbox teeming with Christmas cards from the great, good and all else.

Perhaps none so great, or at least none so iconic, as Bobby Moore. He was staying at the Grand Hotel in Sheffield in the lead-up to England’s World Cup win over Germany at Wembley in 1966. Who cut his hair? The same Steve who just over a decade beforehand was interned in the Lodge Moor Prisoner of War Camp for fighting with the Germans. You could not make it up.

The rest

As I wrote earlier, the person writing on the Sheffield Forum was right: Steve was Ukrainian. When he gained his citizenship he was pictured in the Sheffield Star holding the papers in one hand and in the other, the original painted, wooden Ozzie Owl figurine given to him by the then Chairman.

In 1992, he was on board the first flight from Manchester to newly independent Ukraine. He took cash as well as memories. He supported and loved the family still living there. He nurtured a family of his own, had grandchildren, but even in retirement, still found time to cut the hair of a bespoke list of customers.

Steve died in Sheffield not all that long ago, leaving behind more stories than I could possibly put down in a single article. Perhaps one day, I’ll get his grandson to tell me some more.

But I promised at the start of this piece that this was also a story of how The Pinch came to be. Steve was a Sheffield Wednesday fan. Sam isn’t.

The Pinch

Many years after Stefan “Steve” Bajdala left Ukraine, I’m walking into Wembley with his grandson, Sam. We’re old enough to know better and young enough not to care. We reach security with lit cigarettes. When the guards pat us down for knives, pyros and other contraptions, we hold our arms out like Christ the Redeemer, smoke curling from our fists. The okay comes. We step through the turnstiles — one left, one right — cigarettes still burning. We meet again on the concourse. The Blades lose, of course.

A couple of years later, we’re sitting together on the first day of the season. My knees are knocking together like the flapping wheel of a broken shopping trolley. It isn’t nerves — I just need the toilet — and Sam Bajdala-Cressey will have to put up with that for as long as we sit next to each other. The Blades lose 0–4 to Gillingham.

Between the defeats and the long away trips, between the smoke and the laughter, the DEM Blades fanzine and then The Pinch begin to take shape: part fanzine, part scrapbook, part love letter to Sheffield United and its culture and history, not just the sport. It’s more than a sport.

It starts with stories like Stefan’s: fragments passed down, memories rescued from old photographs, tales told in barbershops and football grounds. Sam designed the fanzine, crafted logos, and turned a teenage idea of bringing back a fanzine into reality.

Stefan Bajdala’s story could have ended in a camp in Sheffield, a name on a list, another life interrupted by war. Instead, it carried on — through kindness, through football, through family. A man once classed as an alien became part of the fabric of a city. His hands, once steady on the barrel of a tank, spent a lifetime holding scissors and shaping much more than hair.

When Stefan was born in Ukraine, no one could have imagined that the path ahead would lead to a prisoner-of-war camp in England, to a barber’s chair in Sheffield, to Bobby Moore and Neil Warnock, and certainly not, given his allegiances, to helping bring a Sheffield United fanzine come into being. But that’s what kindness does — it echoes.

Today, the village where Stefan was born has become a corridor for people fleeing the same kind of violence he once escaped. Some of his relatives still live there, caught between borders and bombardments.

Stefan made it to Sheffield. He was welcomed by Blades and Wednesdayites alike. Whilst I don’t think there has to be a moral to a story, perhaps there is one here: aliens aren’t all that alien, and kind acts can make good things happen, whether it’s offering a smoke, a joke, or maybe a story.

What an interesting and evocative story. My own grandfather was an Italian POW, most likely at Stoney Middleton, who had a brief fling with a local 17 yea old girl (my grandma) whilst working on the land. Unlike Steve, he went back to Naples after the war leaving behind the product of this fleeting romance (my mum*). We never met him, but there is a famous Neapolitan pizzeria with his surname above the door, however it could be a common name there!

*the partial subject of my first Pinch piece.

Oh , that was absolutely fascinating! Thank you so much for sharing. One looks around at a ground full of supporters, never realising what stories they may have in their family history, so it was great to learn about yours.

And you're right: (a) you couldn't make it up; and (b) he did look like Pope John Paul II.

A great piece of history writing; thank you very much.

Sue.