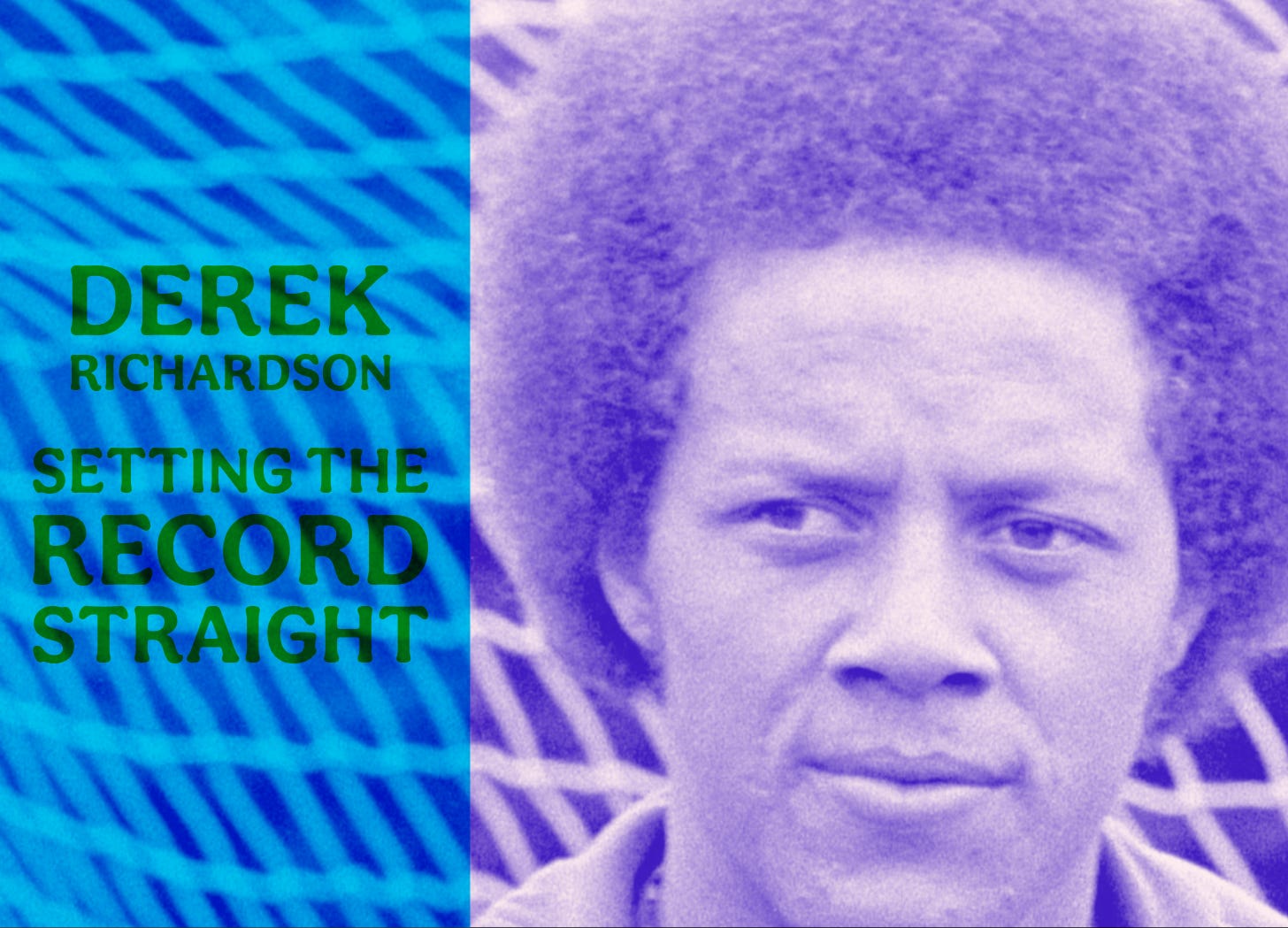

Derek Richardson: setting the record straight

Andrew Wilson spoke with the first black top-flight goalkeeper of the 20th century to discuss his trailblazing career, football's fight against racism – and keeping goal in the Boxing Day Massacre...

Andrew Wilson

When Derek Richardson made his QPR debut against Leeds United in March 1977 he made history, becoming the first black top-flight goalkeeper of the 20th century (keeping a clean sheet for good measure). But amongst Sheffield United fans, he is infamous as the goalkeeper who conceded four in the Boxing Day Massacre, on a day when the Blades under-performed from one to eleven.

Whether you remember him as a trailblazer or a villain, his place in English football history is assured. Or at least it was.

A recent publicity blitz for Alex Williams’ autobiography led to a spate of publications – from The Athletic to The Mirror – naming Williams as the first black goalkeeper of the modern era. Williams is a legend in his own right, playing 125 matches for Manchester City, but he didn’t make his debut until March 1981 – a full four years after Richardson.

As a football historian, I hate to see someone forgotten from the history books. As a Sheffield United fan I particularly hate to see the Blades overlooked in favour of a ‘Big Six’ club! So I resolved to track Derek down to hear his story – from coming through the youth system at Chelsea, to making history with QPR, and playing for the Blades in their darkest days.

And straight away, he didn’t disappoint.

“Alex Williams? I’ve been in touch with his publisher…”

By the mid-1970s, Chelsea were an anomaly: the only London-based Football League team yet to field a black player. But in August 1975, fate tried to nudge them in the right direction.

Long-serving goalkeeper Peter Bonetti had moved to America in the summer, after 16 years at the club. Replacement John Phillips had broken his ankle in pre-season, and back-up Steve Sherwood had injured his back in training. It seemed the only option was to turn to their youth team, where Derek Richardson – born to an English mother and Jamaican father – had kept 40 clean sheets in two seasons.

The press agreed: ‘Richardson all set to make Chelsea debut’, ran the headline in the Daily Mirror. Manager Eddie McCreadie though, interviewed at the time, seemed less enthusiastic: “Richardson has a lot of potential, but I did not want to rush him into League football yet. However, if Sherwood is not fit I will have no alternative.”

Predictably, Sherwood was brought back ahead of schedule, and Richardson was denied his place in Chelsea’s history. The club’s own website describes this as a missed opportunity – it would be another seven years before Paul Canoville became their first black player.

Almost fifty years on, does Richardson remember the build-up to this match? Was he aware he was in contention for a start?

“This was one of the major points in my career,” he recalls.

By now, eight of Richardson’s youth teammates had been given their chance in the first team, ranging from club legends like Ray Wilkins to lesser-known names such as John Sparrow.

“I was ready to play,” says Richardson. “I was disappointed: it was a big thing. Obviously with Chelsea you’re all over the papers, then suddenly there was nothing. Steve Sherwood comes back, plays and that’s why in the end I thought I had to move on.”

It may well have been a blessing in disguise. Bill Hern and David Gleave, authors of Football’s Black Pioneers, describe Paul Canoville as “the only player in our book who was consistently booed by his own club’s fans,” while Chelsea’s website describes how Canoville “suffered horrendous racist abuse from a sizeable proportion [of Chelsea fans]” on his debut.

Perhaps it is no surprise that the one first-team game Richardson did play for Chelsea – a 3–2 friendly win against NK Čelik Zenica – took place in communist Yugoslavia, far away from Stamford Bridge. He remembers the crowd that day “were told when to clap and when not to clap, it was weird.” Alas, such order was not a well-known feature of the Shed End in the 1970s.

“As the years go on, I sit down and think why didn’t he play me?” says Richardson on being overlooked for the first team. “Was it because I wasn’t good enough? No, it can’t be, because I wouldn’t have been there if I wasn’t good enough. They didn’t trust me for my colour, I believe. That’s my view.”

The lack of trust was reinforced when Peter Bonetti was brought back from America the next month, pushing Richardson even further down the queue. Luckily, just as he was looking to leave, a friendly face offered an escape route. Dave Sexton, who had signed Richardson for Chelsea before being sacked in 1974, had been appointed manager at QPR. He soon came in for the teenage goalkeeper. Richardson jumped at the opportunity: “I went from fourth-choice to second-choice, and QPR were in Europe!”

In March 1977 – almost two years after his Chelsea near-miss – Richardson’s opportunity finally came back around. QPR’s first-choice goalkeeper Phil Parkes was injured, and Richardson made his debut against Leeds United in a goalless draw. In doing so, he became the first black goalkeeper to play in the First Division since Arthur Wharton’s sole appearance for Sheffield United in 1895.

Four days later, Richardson tasted victory for the first time, keeping his place as QPR beat Arsenal 2–1. In fact, with Richardson in goal, QPR had a particular habit of upsetting the big teams, including beating European champions Liverpool 2–0 in just his fourth appearance (“I had a wicked game!”). But there was one match in particular that stands out for Richardson – his return to Stamford Bridge.

“That was the biggest game of my life,” says Richardson. “All my friends at Chelsea were playing. They’d just bought [Serbian goalkeeper] Petar Borota, and I thought that should have been me, not him. I was nervous, because I’d moved on and I didn’t want to move on: I was Chelsea through and through.”

QPR won 3–1, and Richardson confesses to still having a recording of the game on his phone. “It was probably one of my best days as a footballer. I was pleased that I went back and proved myself.”

Unfortunately, Richardson’s time at QPR was nearing an end. With Dave Sexton moving to Manchester United, new boss Tommy Docherty signed future England international Chris Woods for £250,000, who took the number one spot.

That summer, however, Richardson was given the gloves for one of English football’s more unusual fixtures, as a team of eleven black players played against a team of eleven white players in Len Cantello’s testimonial match.

“They said every time we get a foreign team over [for a testimonial] it rains, and hardly anyone knows them,” Richardson explains of the match’s organisation. “Let’s have a team from this country, that everyone knows, and make it black!”

In his article about the fixture, Adrian Chiles states “it sounds somewhere between somewhat odd and downright appalling now,” so how did it feel at the time? “I was quite excited,” recalls Richardson. “We might even get a rich black man and he can buy the club!”

The black team triumphed 3–2, and to his surprise it is this match he is asked about more than any other. “It was like a kickabout really, we said no injuries because we’ve got games at the weekend so let’s not go crunching,” says Richardson. “Only afterwards was it more important that the result went our way. We left our mark – there was National Front outside handing out leaflets before.”

In December 1979, Richardson signed for Sheffield United in Division Three for the rather unusual fee of £55,555. However, his time at the Blades was almost over before it began. “The goalkeeper when I signed was Steve Conroy,” remembers Richardson. “On the Monday I played a round of golf with the team. I’ve hit my ball, three of us have gone off the tee and we’re walking up the fairway. Suddenly I hear a big noise, a big bang. Steve Conroy had tee’d off, knowing that we’re walking only 30 yards away, so if he’d hit me in the head I’m dead.

“It’s bang out of order, it’s like shooting a gun at you. His ball had gone through and lodged in my bag. When I turned round and went back to him, if I had whacked him they would have classed me as a lunatic, but he nearly killed me. You’re supposed to wait until they’re 200 yards away! He had to replace the bag, and [our friendship] never really pushed on from there. Obviously he knew I had come to take his place.”

Like many Sheffield United fans who were around in that era, one teammate’s name in particular stands out. “Alex Sabella! He was a fantastic player. Too good for the Third Division. They used to kick him. He was meant for the Premier League where you get time to turn. Some of the Man City players remind me of him.

“He was a wonderful person too. A good family man, and a lovely man to be with. I’m glad I had the time to show him round Sheffield and take him down the snooker hall.”

Reluctantly, we must discuss December 26th, 1979.

“Just before Christmas, we played Southend at home, and it was my debut,” says Richardson. “We won 2–0, I took a nice couple of high crosses and was pretty pleased. We were top of the league. And then the Boxing Day Massacre was the next game.

“I had played against Arsenal [with QPR] and that was a derby, but this was different. It was intense. They scored a wonder goal [in the first half]. Terry Curran – he was a quality player for Sheffield Wednesday – had gee’d up their players a lot. We should have equalised: just before half time, John MacPhail missed from about four yards, and going in 1-1 it would have been nice, but we went in 1-0 down and they scored three more in the second half. We had a strong side, and were above them in the league, but I think something took over that day and the boys didn’t perform... Maybe it was too much turkey.”

It is tough to assign much blame to Richardson for Sheffield United’s relegation to Division Four the following season – he was ever-present until December, at which point he lost his place to Conroy with the Blades ninth in the table. He only played once more as United won just four of their remaining 22 games, ending the season in 21st place.

Ultimately both Richardson and Conroy lost out when new manager Ian Porterfield signed Keith Waugh for United’s first ever campaign in the fourth tier. In March 1982 Dave Sexton – by now manager of Coventry City – came calling for a third time, and Richardson left the Blades after 55 appearances in all competitions. However, he failed to break into the team at Highfield Road, finishing his career in non-league with Maidstone United, where he won the Alliance Premier League (today’s National League) in 1984 in the days before automatic promotion. He also won four caps for the England semi-professional team along the way.

Unfortunately, as Richardson dropped down the divisions, the game’s uglier side became more apparent. “Being a goalkeeper, you’re basically stuck in one position, surrounded by the 18-yard-box, never to come out of that box, and you could hear racism from behind the goals,” recalls Richardson. “Not so much playing for QPR [in the First Division] but later on with smaller crowds, you could hear them from the stands. For me, the way to beat these people was to play well, shut ‘em up, and then suddenly they’re cheering for you. That’s when you know you’ve won.

“When the crowd are taunting you, if you turn round because you’ve had enough, they’ve won – they’ve beaten you, they’ve made you turn. The game’s that way, not this way. But afterwards when it was over, I used to look up and shout ‘anyone wants to say hello to me I’ll be in the bar, come and buy me a drink and we’ll talk then’. So yeah, it was a battle.”

One incident during this stage of his career sticks in Richardson’s mind. “I went to Barnet and my brother was in the terrace behind the goal. Someone said something and my brother leant on him and said ‘sorry mate, that’s my brother there, did you just say something?’, and the geezer went ‘no, he’s a great keeper!’ The guy probably never said another word, ‘cos my brother was a heavyweight champion in the army: when he looked at him, he must have shit himself!”

Other than dispersing prizefighters throughout the stadium to keep peace, Richardson believes stadium closures are the most effective way to rid the game of racism in the modern era: “A fine means nothing: they can pay all day long. But if their supporters can’t watch them play because of what they’ve done... they’ve got to rid them of that evil.”

I put it to Richardson that black goalkeepers are still somewhat under-represented today, but he disagreed: “Do you think so? In the lower leagues there’s loads now. I’m really pleased for them. They’re coming through, I believe.”

In particular, both of Richardson’s old clubs had a first-choice black goalkeeper last season – Wes Foderingham for Sheffield United and Seny Dieng for QPR. Does Richardson feel he helped pave the way? “Maybe down to me and Alex Williams, maybe not. Who knows?”

With Richardson’s story told and the history book well and truly corrected, allow me to add a few footnotes.

First off, Derek wanted to make clear that he was honoured to receive Alex Williams’ book, is proud of his achievements as a top keeper, and wants to place on record his admiration for William’s work with Manchester City.

The Boxing Day Massacre was not Richardson’s only Steel City Derby – he got his revenge later that season, as the Blades triumphed 2–1 in the 1980 County Cup final.

Even though he never played a competitive game for them, Chelsea still send Richardson a hamper at Christmas every year.

And despite causing early editions of Alex Williams’ autobiography to be pulped, the goalkeepers’ union remains in force and the two are on good terms – “he’s gonna send me a copy of his book,” Richardson laughs.

A fascinating piece. I saw Derek make most of his appearances for QPR. A real trailblazer and an underrated goalkeeper.

So glad to see that the historical record has now been corrected.

Thanks, Andrew – that was most interesting.

I love finding out these snippets of information about players long before my time of supporting The Blades; and surviving all that racial abuse with his sense of humour still intact is quite a feat for Derek Richardson.

Sue.

PS. I’m glad history has been righted, too!